Vajrayana Buddhism is the state religion of Bhutan, followed and practised by about 80% of the population. Vajrayana is also referred to as Tibetan Buddhism and is based on a complex philosophical and ritual system meant to provide a path towards enlightenment.

Vajrayana Buddhism is the state religion of Bhutan, followed and practised by about 80% of the population. Vajrayana is also referred to as Tibetan Buddhism and is based on a complex philosophical and ritual system meant to provide a path towards enlightenment.

Broadly, there are three main schools of Buddhism that are practised today; 'Theravada' or 'Hinayana' which translates to ‘lesser vehicle’ or ‘small vehicle, 'Mahayana' and 'Vajrayana Buddhism'. All schools in general agree and propagate the Four Noble Truths, the Eight-Fold Path, and the teachings about karma and nirvana.

'Vajrayana', also known as ‘Diamond Vehicle’, focuses on esoteric traditions and predominantly emerged from northwest India during the seventh century A.D. It is also sometimes called the 'Tantrayana' or 'Mantrayana' (Vehicle of Sacred Utterance), said to be the path that allows enlightenment within a single lifetime. It combines elements of Mahayana philosophy with the esoteric physiological and psychological practices of the emergent Tantric oral literature to form a powerful, unorthodox, and highly successful method for attaining enlightenment. It also includes extremely rigorous practices derived from the tantric yoga of India. After developing tranquillity, freedom and loving-kindness, as encouraged in Mahayana Buddhism, dedicated Vajrayana aspirants are guided through a series of tantric practices by Gurus. The highest of these are lamas, who are revered as teachers. Some are considered as incarnate Bodhisattvas who have realized the Supreme Truth and can help others advance towards it.

'Vajrayana' also refers to the eternal Buddhahood resident in all beings, unsplittable and achieved through the cutting edge of wisdom (prajna). The spiritual exercises of Tantra aimed at identification with the Buddhahood here and now and conceived of the individual as being of the same nature as the universe. So, by self-purification, one could visualize one’s chosen deity or Buddha figure and thus attain unity with it. The highest form of Vajrayana is the use of the subtle vital energies of the body to transform the mind. The practices used to transform the mind are levitation, clairvoyance, meditating continuously without sleep, and warming the body from within while sitting naked or thinly clad in the snow. Vajrayana literature developed late in school, thus necessitating a primary emphasis on the role of the guru or the spiritual master. The teachers utilize mantras, mandalas, mudras and others to bring about dramatic results for their disciples. The great saints of Vajrayana are called Mahasiddhas, known for possessing magical powers.

Mahayana Buddhism which was superseded by practices known as Mantrayana, Vajrayana, Tantrayana or simply Tantric Buddhism is popular in Bhutan. The Buddhism that entered Bhutan progressed over the centuries becoming an ever more subtle and powerful instrument for spiritual achievement. As a Tantrayana, it asserts that Enlightenment can be achieved in a single lifetime. The countless lives that Buddhism had traditionally insisted upon were to be achieved in a few brief years. Since Tantra is of immense power, its methods must be kept secret and only imparted by a spiritual master or Guru. Tantric Buddhism deals with psychophysical experience. It also involves the visualization of deities that are either benign or wrathful. Therefore, Tantric Buddhism has elaborate rituals and a vast pantheon of gods, goddesses, saints and demons. Another feature is the belief in the reincarnation of lamas.

Mahayana Buddhism which was superseded by practices known as Mantrayana, Vajrayana, Tantrayana or simply Tantric Buddhism is popular in Bhutan. The Buddhism that entered Bhutan progressed over the centuries becoming an ever more subtle and powerful instrument for spiritual achievement. As a Tantrayana, it asserts that Enlightenment can be achieved in a single lifetime. The countless lives that Buddhism had traditionally insisted upon were to be achieved in a few brief years. Since Tantra is of immense power, its methods must be kept secret and only imparted by a spiritual master or Guru. Tantric Buddhism deals with psychophysical experience. It also involves the visualization of deities that are either benign or wrathful. Therefore, Tantric Buddhism has elaborate rituals and a vast pantheon of gods, goddesses, saints and demons. Another feature is the belief in the reincarnation of lamas.

The two great collections known as the Kangjur, 108 volumes, regarded as the teaching of the Buddha, and the Tengjur, 225 volumes of treatises and commentaries by Indian masters and other texts, serve as the main source of Buddhist knowledge. The centres of learning are the Dzongs, monasteries, shedras and lobdras.

According to terma (spiritual treasures hidden by great Buddhist teachers), the initial introduction of Buddhism into Bhutan occurred in the seventh century. At that time, the Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo, the 32nd king of the Yarlung dynasty, built two temples in western and central parts of Bhutan (Kyichu Lhakhang in Paro & Kurje Lhakhang in Bumthang) as part of a strategy to pin down a demoness who was ravaging the Himalaya. About a century after the construction of the temples, Guru Padmasambhava, known throughout the Himalayas as Guru Rinpoche, or ‘Precious Teacher,’ arrived in Bhutan, subjugated eight classes of local spirits and made them sworn protectors of the Dharma. In this way, local deities and spirits became incorporated into Bhutan’s Vajrayana Buddhism to the extent that images of them are found at Buddhist temples and monasteries.

The majority of Bhutan's Buddhists are adherents of the Drukpa subsect of the Kargyupa (literally, oral transmission) school, one of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, which is itself a combination of the Theravada (monastic), Mahayana (messianic), and Tantrayana (apocalyptic) forms of Buddhism. The Kargyupa school was introduced into Tibet from India and into Bhutan from Tibet in the eleventh century. The central teaching of the Kargyupa school is meditation on mahamudra (Sanskrit for great seal), a concept tying the realization of emptiness to freedom from reincarnation. Also central to the Kargyupa school are the dharma (laws of nature, all that exists, real or imaginary), which consist of six Tantric meditative practices teaching bodily self-control so as to achieve nirvana. One of the key aspects of the Kargyupa school is the direct transmission of the tenets of the faith from teacher to disciple. The Drukpa subsect, which grew out of one of the four Kargyupa sects, was the preeminent religious belief in Bhutan by the end of the twelfth century.

The advent of Drukpa Kargyupa to Bhutan is very significant since many aspects of Bhutan and the Bhutanese are associated with it. For instance, the name ‘Druk Yul’ for the country and Drukpas for the people originated from the Drukpa Kargyupa School. More still, Bhutan was unified under the Drukpa banner. The system of government is also much in line with the one established by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, an important Drukpa personality. The laws codified by him are the fountainhead of the legal system of Bhutan. The prayers that are chanted and the rituals conducted are much influenced by the Drukpa Kargyupa tradition. Even the origination and the consolidation of the present monastic system are associated with the Drukpa personalities.

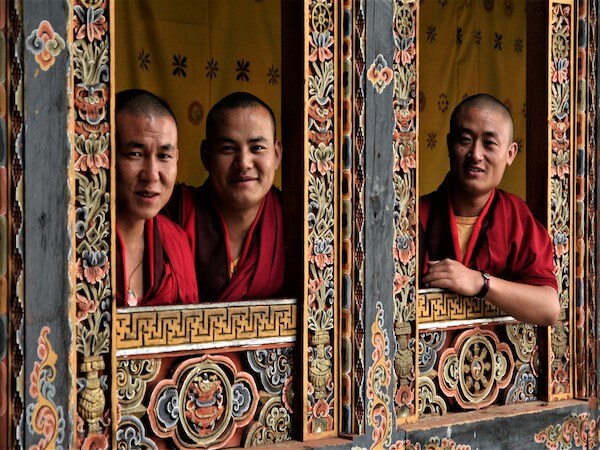

Monasteries and convents were common throughout Bhutan in the late twentieth century. Both monks and nuns kept their heads shaved and wore distinguishing maroon robes. Their days were spent in study and meditation but also in the performance of rituals honouring various Bodhisattvas, praying for the dead, and seeking divine intercession on behalf of the ill. Some of their prayers involved chants and singing accompanied by conch shell trumpets, thighbone trumpets (made from human thighbones), metal horns up to three meters long, large standing drums and cymbals, handbells, temple bells, gongs, and wooden sticks. Such monastic music and singing, not normally heard by the general public, has been reported to have ‘great virility’ and to be more melodious than its Tibetan monotone counterparts.

To bring Buddhism to the people, numerous symbols and structures are employed. Religious monuments, prayer walls, prayer flags, and sacred mantras carved in stone hillsides are prevalent throughout the country. Among the religious monuments are Chorten, the Bhutanese version of the Indian stupa. They range from simple rectangular ‘house’ chorten to complex edifices with ornate steps, doors, domes, and spires. Some are decorated with the Buddha's eyes that see in all directions simultaneously. These earth, brick, or stone structures commemorate deceased Kings, Buddhist saints, venerable monks, and other notables, and sometimes they serve as reliquaries. Prayer walls are made of laid or piled stone and inscribed with Tantric prayers. Prayers printed with woodblocks on cloth are made into tall, narrow, colourful prayer flags, which are then mounted on long poles and placed both at holy sites and at dangerous locations to ward off demons and to benefit the spirits of the dead. To help propagate the faith, itinerant monks travel from village to village carrying portable shrines with many small doors, which open to reveal statues and images of the Buddha, Bodhisattvas, and notable lamas.

To bring Buddhism to the people, numerous symbols and structures are employed. Religious monuments, prayer walls, prayer flags, and sacred mantras carved in stone hillsides are prevalent throughout the country. Among the religious monuments are Chorten, the Bhutanese version of the Indian stupa. They range from simple rectangular ‘house’ chorten to complex edifices with ornate steps, doors, domes, and spires. Some are decorated with the Buddha's eyes that see in all directions simultaneously. These earth, brick, or stone structures commemorate deceased Kings, Buddhist saints, venerable monks, and other notables, and sometimes they serve as reliquaries. Prayer walls are made of laid or piled stone and inscribed with Tantric prayers. Prayers printed with woodblocks on cloth are made into tall, narrow, colourful prayer flags, which are then mounted on long poles and placed both at holy sites and at dangerous locations to ward off demons and to benefit the spirits of the dead. To help propagate the faith, itinerant monks travel from village to village carrying portable shrines with many small doors, which open to reveal statues and images of the Buddha, Bodhisattvas, and notable lamas.

The Bhutanese constitution, adopted in 2008, identifies Buddhism, which ‘promotes the principles and values of peace, non-violence, compassion and tolerance’, as the ‘spiritual heritage’ of Bhutan. Although Buddhism is elevated as the spiritual heritage of the country, the Constitution grants freedom of religion.